A Word

The Marathon Diaries:

by Jacqueline Alexander

First published in the Henley Standard 2012

As a twenty-a-day smoker with little inclination to visit the gym, Jacqueline Alexander could only be considered a PUP (Pathetically Unfit Person). Sir Steve Redgrave, on the other hand, was a five time Olympic Gold medallist and remained a fit and healthy athlete even though his rowing career had ceased six years earlier. Embarking on the same challenge, Steve and Jacqueline decided to compare notes as they trained for one of th emost famous races in the world.

We were walking back to the school when he took my hand.

I looked to him and smiled. He smiled back at me, then looked away. His face was weighted with responsibility but laced with a steely determination that I was sure would help him overcome all the challenges that he would inevitably have to face.

I had met Abdullah for the first time just three hours earlier. Aged just 14, he is responsible for his three or four younger siblings. He walks for 50-60 minutes to get to school. He is a keen photographer with a good eye for a shot, but neither of us knew that before today, he has never been behind the lens before. He is strong, kind, intelligent and protective, my four favourite attributes in a person.

Having visited Abdullah's home, two beds and seven people helped me to deduce that Abdullah shares both his day and night with his family. His parents are farmers but they are not working today, maybe not tomorrow, either. They may not work until the rain arrives in June or July and the rice fields come alive with people and produce.

I ask Abdullah if he wants to become a farmer. "No, I love learning," he replies. "I want to be a teacher." I feel hope flooding through every vein in my body and gently squeeze Abdullah's hand in silent encouragement.

In The Gambia, or, in my limited experience of The Gambia, children offer their hands, and their hearts, openly and willingly. It is touching, endearing, and like a breath of fresh air to someone who comes from a world where it is increasingly difficult to offer an open heart without risk of suspicion or, at the very least, accusations of naivety.

Abdullah is different to the other children though. At 14, he is the older than most I have encountered at Kwinella Lower Basic School and he is more measured in his emotional responses. He seems to take on the role of tour guide, informative but detached.

Our journey to his home is filled with questions and answers, my questions, his answers. I quickly learn that if he does not understand a closed question, he will always answer 'yes'. Open questions follow as I try to find out more about a life I cannot possibly hope to understand in just a few hours.

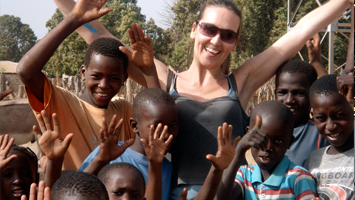

As our journey continues along the dusty lanes, we attract attention from the villagers, or more precisely, I attract attention from the villagers. A tall, white, woman walking along with, by now, approximately 18 young children must look odd to the inhabitants of Kwinella, a rural Gambian village with a population of 4000 spread over a wide, and largely unseen, area.

Women rush from their huts to the rusting, corrugated tin fencing that surrounds their compound, and shout over to us in Mandinka, their local tongue, demanding information. Who is she? Where are you going? Where is she from? What are you doing? Each time, Abdullah patiently answers their questions, and then relays both the question and answer to me in broken English.

As we arrive at our destination, at least 10 of the children who have joined us pile into one of two thatched huts that comprise Abdullah's home. His father is in bed in the other hut. Another boy, around the same age as Abdullah, is asleep on a makeshift bed in the corner of the room. Abdullah tells me the sleeping boy is his best friend, who has been up since 5am as he had worked before going to school. He is 15.

The children filling the small room all look at me expectantly. Abdullah's sister, aged three, climbs on my lap and his younger brother sits next to me. The other children gather around. I am unsure what to do. I notice an old portable cassette player that would have been state of the art in 1985 and ask Abdullah if he likes music. He smiles and nods as he gets up to play a tape. The music system is hooked up to an old car battery which, we discover, is flat. Abdullah's face falls in disappointment. I remember that my highly conspicuous iPhone4 has around 200 tunes on it, so out it comes. Faces light up and the mini mob surrounds me to look at the phone as Hey Soul Sister blares out. At home, I would normally be dancing around my sitting room by the third beat but somehow it doesn't feel right as the children's fascination with the technology submerges any interest in the music itself.

I remember how the children here love a camera so I touch the camera icon and we are off. Anticipation fills the room as everyone requests, nay, demands, their photograph is taken. They all brim with excitement as they fight for priority.

Abdullah takes charge of who will be photographed in what order. He organises the groups, he chastises the clowns who insist on trying to get in every shot, and, when each child has been sated by the instant record of their image, he calls the photo shoot to a halt. It is time to visit his friend's home.

En route, we stop at the water pump. The locals waiting their turn at the pump are only too happy for me to have a go so I give my camera to Abdullah and start to pump water into the waiting five gallon tank. Once the photograph is taken, Abdullah calls to me to stop. "It's done, Jacqueline, it's done." It feels cheap to take advantage of a quick photo opportunity so I continue to fill the tank, much to the villagers delight. It still feels like cheating as I walk away, only marginally better than walking away earlier. Abdullah disagrees and seems strangely proud of me. I am unsure what has caused this, but I am pleased. Very pleased. Abdullah is no longer just my tour guide.

As we arrive at the next compound, I am intrigued by the different aspects of life all packed into one front yard. The grandmother sits on a stone platform with her feet up but without support for her back. She draped in a rich mix of gold, cream, and black tie dyed fabric and an air of authority. Her warmth reveals itself when I offer my hand and thanks for allowing me into her home. Behind her, a quieter, less authoritative, but no less warm, woman sits with a plastic tub, I am not sure whether it is for washing or some other form of work but she doesn't speak any English so I am left guessing.

A girl pounding millet beckons me over and offers me the second mortar to help. She indicates that we will take it in turns to pound. We quickly find a rhythm that puts a broad smile across her beautiful face. Her name is Binta.

Abdullah, still in charge of my camera, takes a photo and I am again faced with the embarrassing request to stop work. On this occasion, I am saved by Katrina, my fellow volunteer, who is visiting Abdullah's friend's home within the compound. Katrina wants to take over my position as second 'pounder' so I take over as photographer.

Children surround us, excited and intrigued as two strangers take an interest in their lives, and their welfare, and probably look very odd contributing (a little) to the daily tasks required to keep the compound running smoothly.

Time is flying by as we decide it is time to leave and make our way back to the school. I don't want to go but I don't want rebellion to be my lasting legacy in this village that is slowly but surely securing a place in my heart.

We set off on the long, orange coloured, dusty roads towards the school, but at a slow pace. Abdullah may be walking slowly because of the unrelenting heat, or because he is still taking advantage of every photo opportunity along the route; donkeys, goats, cattle, dogs, mango trees, baobab trees, cashew nut trees and friends are all deemed interesting subject material. He is not wrong.

I am walking slowly to prolong the journey. I realise this has been a day I will never forget. This is the moment Abdullah takes my hand.

As we near the school, Ousman and Lamin Daffeh pull up in their car, one of only half a dozen vehicles I have seen in the last week and a half, with at least two of them belonging to our group.

Lamin Daffeh runs Fresh Start Foundation, the charity that organised this visit to The Gambia, and is the man I had first contacted over a year ago, asking if I could volunteer to help with his work in Kwinella and the surrounding villages.

Over the next few months, the first signs of friendship had started to bud as we got to know each other but in the last week that friendship has resulted in a love affair, my love affair with Gambia. It is one that I think will last a lifetime.

by Jacqueline Alexander

Copyright 2012

Articles

- Boris Johnson Interview:

The day after the day before - Feature:

Peace flowed through... - Feature:

A love affair - Feature:

Home from home - Sir Steve Redgrave:

The Marathon Diaries - Week One:

The Phone Call Week Two:

Keystone Cop Week Three:

The Cold War Week Four:

A Tough One Week Five:

Going Bananas Week Six:

Smiling Inside Week Seven:

Fruit Juice and Fresh Air Week Eight:

Ow, ow, ow Week Nine:

Humbled Week Ten:

Mud Week Eleven:

Miracles Do Happen Week Twelve:

For I have Sinned Week Thirteen:

One for Luck Week Fourteen:

The Moment of Truth - Column:

Web Watch - A painful talent? Just six words Let's get biblical That 'uh-oh' moment Keeping it real Ever the Twain A conflict of interest Think inside the box Creative differences Here lies common sense A blast from the past And it's goodbye from them

- Column:

Single in SOHO - Cabin fever I can't be bothered The curse of SOHO

- Column:

Just a half - I've been abandoned The river of pain I've fallen in love An uphill struggle Oh no! Sneezes, sweat and tears